Emily Jackson 1909-1993

Memory and the distance traveled—the painterly life of Emily Jackson

Gregory O’Brien

We are always at the beginning of seeing. —Philip Guston

Art is about what religions about, getting you airborne. Getting you out of this box, which is life, into the expanding universe. —Rosalie Gascoigne

The trinity of virtues ascribed to colour: what it is, what it can represent, what it can remind us of. —Trevor Winkfield

Leaving aside for a moment mind and body, a painting is a journal of the hands progress—across the primed surface, or from paint-tray to sheet of hardboard and back again. Painting is, firstly, a verb; only later it becomes a noun. In the year 2016, I would be surprised if someone hasn’t already invented an electromechanical device—a kind of adjusted pedometer—to measure the distance a brush travels during the creation of a painting.

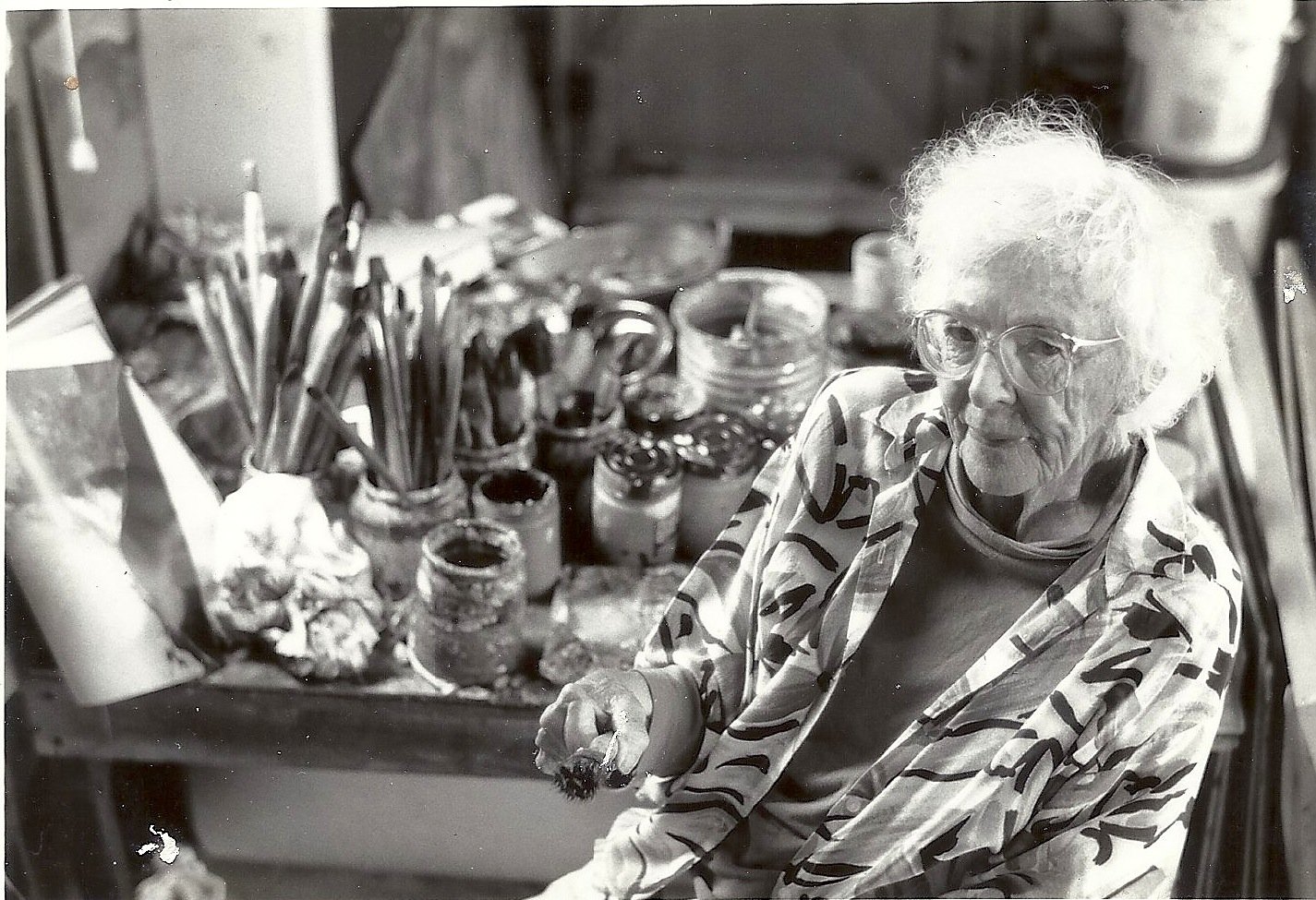

Fig. 1: Emily in her studio, 1984

Beyond any movement of hand or arm, the act of painting lays claim to the body of the artist and the space around him or her—just as it consumes moments, hours, days and weeks of the artists life. Emily Jacksons paintings cover a lot of ground in every sense—and her letters and written journals are illuminating annotations and footnotes to a painterly oeuvre which is also journal-like in the progress it records, day to day, from one place to another.

Through the last twenty-five years of Emily’s life, her churning, percolating brush-strokes sifted through place and memory, tracking rather than tracing, in a literal sense, immediate and remembered environments. The world they assay is a destabilised, activated zone. Within a single painting there are moments of wetness and drought; one moment the daylight is dazzling, the next it has been squeezed, lemon-like, from the atmosphere. The paintings register the high-keyed shimmer of a river or the shifting weight of the sky on the Desert Road or Middlemarch landscape.

Various commentators have, on earlier occasions, applied the term Impressionism, unsatisfactorily, to Emily Jackson’s work. In fact, the paintings stand their ground somewhere between Impressionism and Expressionism, playing upon both the optical nerve and the nervous system of the viewer. She had little interest in the silky veils of straight-ahead Impressionism or the exacting Pointillism that ensued (‘POINTLESS POINTILLISM’, as the art school graffiti goes.). She sought a grittier, more elemental engagement. Closer, in this regard, to Petrus van der Velden, her brush-strokes are unfettered and seldom come to rest on a single point or line; her paintings are made up of marks rather than motifs. She paints the bush but seldom delineates a single tree; she conjures a tempestuous sky but hardly ever a solitary cloud.

Fig. 2

In one of a group of photographs taken by Emily Jackson’s daughter Juliet in 1989, (Fig. 1) the elderly artist is parrying with her paintbrush. Her hand locks around the brush while her body inclines to the left, as if she has been swept aside by a strong gust from an open door or window. The light, coming from the right, appears to be propping her up. Capturing the artist mid-gesture, the photograph reminds me of the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti’s paean to that staple of the painter’s studio, the brush:

To you, music-conjuring wand,

Conductor of the seas which set

The canvas, as you wander, silent, wet

Across the night, half-light, & dawn.

[translated by Carolyn L. Tipton]

In the photo above (Fig 2), Emily’s hand and brush are all but merged into a single implement. Her fingers are visibly contorted by the arthritis which she had developed in her late teens. Remarkably, given this condition, she also played the piano with gusto and was a competitive croquet player until well into her seventies.

Elsewhere in his collection, On Painting, Rafael Alberti meditates on the artist’s hand, wondering what vestiges of inner life the act of painting can bring to the surface, and what exactly of the world in front of the canvas can the hand deliver to the work-in-progress:

To you, cross-canvas traveller, helpmate,

Bear of to the stalk that generates

Blossoming creatures, marvellous & ardent …

For the paintbrush, you are not an open rose:

You make your living happily half-closed…

Fig. 3

Juliet’s photograph (Fig. 3) captures something of the urgency of Emily’s work, and also its concentration of physical and mental energies. Yet possibly the most striking thing about this image is that we see the artist from the perspective of the painting before her.

Emily’s brush advances directly towards us, with her frail hand holding on to it for dear life. If the painting had eyesight, this is precisely what it would see.

Emily Jackson was born in Levin in 1909, and virtually all of the first half of her life was spent in Taranaki. When, in her fifties, she began painting seriously after the family had moved to Auckland, it was southward, in the general direction of her childhood, that she was drawn. Numerous car-journeys in the 1970s and 80s were not only acts of discovery but also of recovery, of reoccupying formative territories. With her husband D’Arcy a non-driver, it was Emily who took the wheel on these excursions. Her daughter Bronwen recalls how, during Emily’s later years, when her arthritis had made driving even more challenging, she delegated control of the gearstick and handbrake to D’Arcy (in the passenger’s seat) while she concentrated on the steering wheel and pedals. As a counterpart to these heady but exhausting encounters with Coromandel, Taranaki, the Central Plateau and elsewhere, the garden outside Emily’s studio in Mount Roskill also held considerable sway over her art. Of the garden during this time, Bronwen remembers a profusion of ‘lasiandra, impatiens, bougainvillea, weigela, virgilia, hydrangeas, roses, jasmine, cinerarias, buddleia, and a tub of bromeliads out the front... There were lots of trees—a huge willow tree, juniper myrtle, oak, fig, hibiscus, bottle brush, liquid amber, parapara, and fruit trees: lemon, mandarin, feijoa and guava.’

With its profusion of life-forms, the sub-tropical garden not only served as her colour chart, it was also something of an aesthetic model, accommodating chaos and happenstance as it did careful planning. It was D’Arcy who managed the practical garden work, leaving Emily free to observe the rituals and systematic procedures of gardening—pruning, staking and replanting. The garden offered her an education in the effects of light and shade, surface and texture, and the inter-relatedness of forms.

Despite her increasing command of the oil and then the acrylic medium, particularly as the 1970s progressed, disorder and the potential for disaster remained integral components in Emily’s painterly method. (Her less successful paintings are those in which she plays it too safe and the result is formulaic or simply too agreeable.) Like the landscape paintings of M. T. Woollaston, with whom she has often been associated, her best works are acts of brinksmanship. They work because they almost don’t.

New Zealand art history will most likely place Emily Jackson’s work in a line of independent 20th century landscape painters, of whom Woollaston is the central figure others would include Doris Lusk, Margot Philips, Lois Mclvor and, more recently, Gerda Leenards, Barbara Tuck and Johanna Pegler). Compared to Woollaston’s work, Emily’s colour schemes are aromatic, humid and at times even florid. (I am reminded of the smell in her shed/studio—the pollen-dust and the fecund garden-smell, the scent of mouldering leafage and fallen fruit, merging with the smell of art materials and the under-shed dankness.)

Whereas Woollaston (who was one year Emily’s junior) relished signs of human intervention on the land—fence-lines, a barn or farmhouse, cultivation, a road—Emily’s works are nearly always stripped of such detail. In their brush-work, elementalism and philosophical underpinning, however, her works attest to lessons learnt not only from Woollaston, but also from Colin McCahon, whom she first met in the early 1970s. McCahon offered generous advice through the following decade. He was impressed enough with her work to visit her studio a number of times, encouraging her to paint, as she noted in 1971, ‘abstract landscapes in a very free way... he encourages me in my use of line, or what he calls “writing”, and very loose application of paint...’

The bulk of Emily Jackson’s oeuvre was produced in Auckland during the 1970s and 80s—a vital and diverse period in the city’s cultural life. Encompassing the dour Holyoake/Muldoon era and the brief optimism of Lange’s Labour government, her journals look beyond the studio and her busy, immensely satisfying family life to observe the coup in Fiji, the death of Colin McCahon... It was a particularly colourful and dramatic time in the Auckland visual arts scene, with a burgeoning women’s art movement (in which Emily’s daughter Juliet was a major presence). There was also something of an eruption of painterly activity in the city’s suburbs, with Stanley Palmer and Pat Hanly at work in their Mount Eden studios; Tony Fomison was painting in Ponsonby; Pauline Thompson, Peter and Sylvia Siddell were presenting familiar aspects of the urban environment in a strange, new light; Pamela Wolfe and Claudia Pond Eyley were producing vivid, almost diaristic accounts of domestic life in contemporary suburbia. Everyone was, in the parlance of the times, doing their own thing.

Emily exhibited at Gallery Pacific, in Endeans Building just off the foot of Queen Street—an unassuming but lively gallery, run by architect Noel Biere and his wife Annette. All kinds of people would drop by the gallery—I remember historian Keith Sinclair and a bevy of poets including Karl Stead and Riemke Ensing; on his weekly round, art critic T. J. McNamara, with his cape and cane, made a regular appearance, and there was an intermittent stream of visitors who had missed their buses at the nearby depot. Protest marches would convene around the corner in front of the Post Office—this was the 1980s, remember—and the gallery was hardly a hundred metres from Marsden Wharf, where the Rainbow Warrior was blown up in July 1985.

Samoan-born Fatu Feu’u had his first exhibitions at Gallery Pacific, as did Kura Te Waru Rewiri (Kura Rewiri Thorsen). With Australian painter-printmaker Noel McKenna, I exhibited at the gallery in 1984 and my first book of poems was launched there two years later. In the very loose constellation of that gallery, Emily Jackson was the senior figure. Her paintings were at once radiant and brooding; the bright, natural light from the street outside suited them well. I was not the only young artist to be impressed and challenged by the gusto and physicality of her work.

In Emily’s writings from those years, we encounter the same incisive and candid intelligence and responsiveness that we find in the paintings. She was clear-headed enough to sort out good from bad Woollastons (which is not always easy) and adaptable enough to recognise the strength of a recent arrival like John Reynolds (who, deservedly in her mind, won the 1988 Lindauer Art Award). She emerges, in her writings, as a perceptive critic. While admitting Frances Hodgkins is ‘probably the best woman painter ever to work permanently in England’, she has reservations about a structural approach which leaves elements ‘all too isolated and floating—like little birds’ nests floating on a stream...’

Emily’s position was that of an independent artist, but not an outsider. She kept a weather eye on the visual arts culture and was very much in the swim of things, while keeping resolutely to her own path.

That Emily Jackson was a North Island croquet champion attests to her tenacity and concentration, not to mention breadth of character and versatility. While croquet is a fair-weather sport involving cleared, flattened earth and straight, measured lines, Emily’s paintings are intuitive and impulsive; they favour stormy and inclement conditions, and the landforms are anything but groomed and cultivated. A game of croquet would be inconceivable in even the most mannered Emily Jackson landscape.

While, for the croquet player, the surface of the earth is a means to an end, for a landscape-painter it is an end in itself—albeit an open end, strewn with possibilities. (As the French painter Pierre Tal-Coat wrote; ‘Landscape is the great metaphor.’) I doubt Emily’s fellow croquet club members would have coped with the degree of Romantic identification manifest in her 1983 journal; ‘I try to paint myself into every hill, cliff, river, road, bush, cloud and sky, so that when I am painting I become for a while the landscape, with its atmosphere and magnificence.’

Emily’s paintings are characterised by a sense of not quite being in a landscape, but of having been in one. Rather than enact the experience of walking into or across a place, their movement is that of drifting, in memory, through or above different territories. At the same time, they are an energetic embrace of the moment of their making—the colourful activity of each day inside and around the artist’s beloved Garden Shed.

Emily’s letters and journals record, just as the paintings do, days in which she must have felt caught in the euphoric updraft of her art. They also embody days when the miraculous business has become unyielding hard work. Such is the life of a painter. While William Wordsworth’s notion of art as ‘emotion recollected in tranquility’ was close to her heart—as it was to so many of her generation, including Woollaston and McCahon—the works also present a compelling inversion of that statement. Emily Jackson’s paintings, joyfully agitated rather than anguished in their conception and execution, are also instances of ‘tranquility recollected with emotion’.

[From: Emily Jackson, A Painter’s Landscape, edited by Bronwen Nicholson]

Emily Jackson - artist

Juliet Batten

When Emily was a girl she loved the paintings of her uncle Walter Tempest, RA, that hung in the house and in the Sutherland’s place along the road. They had bought the best of the Tempests, and when Emily went to visit said oh, look at Millie – she’s not interested in anything we’re doing – she’s only interested in the paintings.

She was always drawing faces - profiles of her father and brothers and sisters. Emily told me that one day in her early teens she climbed the tree in the plantation with a bit of sketching paper and a box of water colour paints and did a painting looking up Matai Street ‘While doing it I thought, this is hopeless - I'll never be able to paint, this is terrible; but when I brought it inside I thought, this is like what I saw’. It was a process she was to repeat again and again - seeking to put down on paper the landscapes that inspired her, always feeling she couldn’t match the vivid shapes and colours of her imaginative vision.

Art school or becoming an artist were impossible for a young Inglewood woman like Emily in those days: ‘I never saw an art book - no-one painted in those days', just as was her dream of becoming a writer: ‘we didn't know anything about things like that really - they were just side-lines'. She trained as a teacher in Wellington, doing part of a degree in psychology and philosophy at the same time, extramurally without tuition. When she returned to Inglewood to start teaching, books were unobtainable, and she had to give up her university studies .She lost her teaching job when she married because it was the Depression and married women were not allowed to hold jobs.

Her energies went into raising her five children, but her creativity soon found expression. When we were young, Emily covered our bed heads with scenes from Beatrix Potter, and she and my father made a set of Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs; she painted them on plywood and he cut them out and mounted them on the wall. She played the piano, read books, and made glass pictures with chocolate papers.

Oakura, 1954

After being encouraged by art specialist Don Campbell, Emily and her friend Laddin Grant, who had a baby Austin car, went out in the weekends painting. Once they were chased out of a paddock by a ram, another time by a bull, and yet another by a swarm of bees. We children often went too, but knew not to interrupt her when she was at her easel; she would be so absorbed. At Oakura Beach there was a storm; we never forgot it because Emily sat out there doing a tiny wild grey painting that captured the mood completely. Even though on the outside Emily may have looked like a Sunday painter, she later said I never thought of painting as a hobby I just knew I wanted to keep on painting.

Her first art book was given to her on leaving Inglewood when she was 46 years old; it was on Renoir. After arriving in Auckland she bought Thames and Hudson and other art books, which she would study constantly. She loved Arthur Hipwell’s criticism classes at the ASA, he talked about Cezanne, Monet, Turner, Japanese prints, and fed her mind.

A whole new world was opening to Emily in Auckland, where three of us children were now going to university She made friends with Betty Curnow, who insisted she get Colin McCahon to see her work. She took her work over to his place in Newton, and couldn't take her eyes off the most wonderful painting, high on the wall: ‘I was absolutely struck by it'. It was one of McCahon’s Titirangi paintings. He studied Emily's work carefully: ‘out of these five, there’s one you'll be able to keep for two years’, he said, then turned over one of the works to see a discarded painting on the back: ‘Now that is a piece of major painting’. Six months later Emily had already moved beyond the work that McCahon said she could keep for two years she painted over it. McCahon visited her many times, giving honest criticism that helped her move forward; then he told her, Ring Noel Moller. He might give you an exhibition'. Emily was then 63.

When she visited, Noel Moller said there’s another woman been asking, about the same age as you, and I said I’d put one in the window. When Emily returned with three of her paintings, he offered her an exhibition straight away, saying, that’s wonderfully free work. I didn't expect anything so strong from someone in your age group. That exhibition was a turning point. Before that, Emily's ambition had been to produce two paintings a year that she could keep; now she was being asked to produce 30 paintings in three months. She went home and did it. At the exhibition, she sold 11, had an excellent writeup from Hamish Keith who found the works full of drama, and was referred to as having one of the major exhibitions of the year in T.J. McNamara’s annual review.

Until that time, she had sold only two paintings: one to the Society of Arts and one to David Lange’s mother, whom she’d met at an art class. Emily found it hard to put a price on the painting and said £7, but Mrs Lange said: ‘no, I'll give you £12', which was ‘riches’ to Emily.

She was so modest that when she entered paintings in the Bledisloe Medal award, she never expected to get them accepted, and was more surprised than anyone when she won the medal.

From that first show at Moller’s, Emily just went on, exhibiting every year. Winter was her painting season, and summer when she played croquet, establishing herself as one of New Zealand s top players. By 1984 she was painting through the summer as well, going into herstudio every spare moment.

She loved nothing better than to be out in her garden studio painting, while my father made frames at his work bench. She was always totally absorbed in her work, drawing on stored up memories from their many trips through the New Zealand landscape. Because her arthritis eventually made painting from nature impossible, Emily developed an extraordinary visual memory. On their trips they would stop the car at places that inspired her; she would gaze at the landscape, storing up her impressions; D’Arcy would take some photos, and they would drive on. Later, she used the photos as triggers for the wealth of visual memory that she had stored up, especially of the movement of the weather, the shifts of light and shade, the cloud shadows skidding across the planes, or weird rock forms rearing their heads into the vast Otago sky. Her output was extraordinary; despite her physical limitations, she was energised beyond what seemed possible.

One day in March 1985 she called in on her way back from a day’s croquet and told me she had done four large paintings the day before, two of them almost complete, and her arms were ‘quite tired' - but it had made up for the day before when she was looking after her grand daughter and couldn’t paint at all. She was then 75. Later those big paintings would come inside, where she would gaze at them for days, then take them out to the studio for more changes. She was always looking critically at the work she’d done, sometimes even getting it taken out of the frame in order to be altered.

The remarkable thing about Emily was the interaction between her intelligence and her inspiration. From scant beginnings she moved ahead, drawing on whatever she could get in the way of instruction or education, always moving forward, never satisfied with her own achievements. It was as if in her own mind something great was always forming and she was forever striving to catch up with it. Even in the last months of her life, when she was bedridden and extremely ill, she kept gazing at her last paintings, finding what needed altering, and applying the final brushstrokes, as her energy allowed, to the paintings which she had propped up over the bed.

She would never promote her work while she was alive, and resisted being interviewed. Now it is time she gets the wider recognition she deserves.